adopt the RAnch Wall station

-

ADOPTED BY ANONYMOUS - THANK YOU!

Located within a stone's throw of the border wall, the Ranch Wall Station is an embodiment of Humane Borders' lifesaving mission and what can be accomplished when we work with private property owners who put humanity before politics.

Ranchers who support our work tell us they don't want to see people dying on their land. And our water is for all. So this station is dedicated to anyone who finds themselves in trouble on this lonely stretch of border wall road--migrants, cowboys, hunters, construction workers, Border Patrol agents, and more recently members of the U.S. military.

We are all human and we all need clean, safe drinking water. The Ranch Wall Station represents our shared humanity and the compassion that residents of the borderlands have toward all who travel through this part of the world.

PHOTO CREDIT: Mike Green

Adopt the Cow Pasture station

-

Adopted by The Church of the Palms, Sun City AZ - Thank you!

Situated on a private ranch only a few miles from the U.S./Mexico border, the Cow Pasture Station lies on desert grasslands that teem with wildlife and wandering ranch animals.

Volunteers often see cows resting in shady spots beneath trees, while horses greet us on bumpy dirt roads. Humane Borders was asked by the property owners to place a barrel here after the owners noticed migrants attempting to get water from pipes and cattle troughs. The kindness of the ranchers and willingness to allow volunteers on their land helps us make safe water available for everyone, especially in an area where we find signs of recent migrant activity.

PHOTO CREDIT: Mike Green

Adopt The Bates Well Station

-

Adopted by the Rasp Family - thank you!

Bates Well Station is one of fourteen stations we maintain in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The station is named after nearby abandoned Bates Well Ranch, protected under the National Register of Historic places. The ranch is located off of the road that turns into the Camino Del Diablo, where many migrants have perished over the last two and a half decades. Daytime temperatures in July and August reach well over 120 degrees Fahrenheit, and scant vegetation offers little hope of shelter from the sun’s scorching rays.

Adopt the Pearl Station

-

adopted by Dr. Edwin McGroarty - thank you!

The Pearl Station is situated on private property, on the land of a concerned and caring Arivaca citizen. When we asked the landowner why she christianed the station "Pearl," this is what she said:

"Our water station is named after the tiny camping trailer that we love to travel with. The feeling we get from being inside it is like finding safe haven in a beautiful oyster shell.

During our years living in the desert, we have met many migrants looking for a safe haven, and we felt blessed whenever we were able to provide for their physical survival and would encourage them to pursue their dreams. We know that many more have passed through when we were not there to help. Being part of the Humane Borders water station program gives us the chance to provide clean water for all travelers whether or not we are there in person, and to show them that we care."

Adopt the Duvall North Station

-

ADOPTED BY ANONYMOUS - THANK YOU!

One of the saddest realities that those of us doing desert humanitarian aid have to confront is that migrant travelers sometimes die very close to a well-traveled highway, within shouting distance of someone's house, or near water supplies that we've placed in the desert. This is the case with 35-year old Jovita Garcia Ortis, who died just 600 yards northeast of our Duvall North Station.

While migrant travelers walking in daylight can often spot one of our blue flags flying on the horizon above our water stations, this isn't the case with migrants crossing at night. This was something that Operations Manager Joel Smith recognized, and as a result, with the permission of land officials, he began placing solar lights on water stations.

Adopt the Jackalope station

-

PENDING

The Jackalope Water Station is one of a number of water stations that we maintain on City of Tucson (COT) lands located near Brawley Wash. In 2000, a COT official found the body of a young woman in the area, a desert traveler who died searching for a better way of life. The memory is one that will stay with him for the rest of his life. As a result, Humane Borders placed a half a dozen different water stations in the area to help prevent migrant deaths.

Adopt the Arivaca Humanitarian Aid OFFICE Station

-

Adopted by the Zelenda Foundation - Thank You!

The Arivaca Humanitarian Aid Office Station is one of two we've established in downtown Arivaca. In 2022, Arivaca residents were shocked when they learned that two migrant travelers had died from heat exhaustion near the town's center. As a result, Humane Borders was asked to establish this water station on the main street of Arivaca with the objective of raising local consciousness about migrants dying so close to home. The ABS Station is situated in front of the Gathering Place, an educational and skill-sharing space for Arivacans of all ages. The space is also home to People Helping People, a non-profit that is dedicated to demilitarizing the border zone and supporting residents in providing humanitarian aid to people in distress in the desert.

Adopt the Growler Wash Station

-

Adopted by Bob and Antonia Davis - Thank you!

Growler Wash Water Station is one of eight that we maintain in the hauntingly beautiful but unforgiving Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The station is situated in a dry wash in sight of the formidable Growler Mountains in an otherwise vast, flat, desolate landscape. Because the land is so flat, there are literally thousands of "trails" that lead to nowhere. Many migrants traversing this desert terrain will walk through Organ Pipe and then Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge until they find themselves in the Growler Valley. The instruction many have been given is to keep the Growler Mountains on their right until they can make it to Interstate 8. Tragically, it's humanly impossible to carry enough water to go the distance.

LOOKING WEST FROM CHILDS MTN AT THE EAST SIDE OF THE GROWLER MTNS. PHOTO CREDIT: GENE O'MEARA

Adopt The Ruby station

-

Adopted by the Zelenda Foundation - Thank You!

Our Ruby Station is situated on private property off of Ruby Road between downtown Arivaca, and Ruby, a ghost town positioned just ten miles north of the border. In 2022, two migrant deaths occurred in the area, one of them very near Arivaca's town's center. Dismayed, a number of Arivaca residents reached out to Humane Borders to ask us to place three different water stations in the area. The concerned owner of this property has lived on the land for many years, and has often found migrant belongings on her land.

Adopt the POLARIS Station

-

Adopted by Kirk Astroth - Thank You!

Polaris is one of five water stations on our Avra Valley route, Situated near a riparian area that lies just south of the station, the area has witnessed a lot of migrant traffic over the last twenty-five years.

This station is also special because it is named after the North Star, prominent not only in the night sky, but also in the Humane Borders logo featuring the Little Dipper constellation. The North Star served as a beacon to freedom for Black people escaping the bonds of slavery, and today it is used as a guiding light for migrants finding their way to El Norte.

Adopt the Eddie Canales Station

-

Available for Adoption

Eddie Canales was a colorful, outspoken human rights advocate and was dogged in his pursuit for justice for immigrants, undocumented or otherwise. In 1968, he volunteered with the United Farm Workers, going on to work with the Texas Farmworkers Union to improve living and working conditions for farm workers in South Texas. In 2013, he founded the South Texas Human Rights Center in Brooks County, and was responsible for the placement of over 200 water stations along the Texas border, helping to save an untold number of lives.

Canales was featured in the documentary What's Happening In Brooks County, and was one of several influential actors who compelled the government to exhume the unmarked mass graves of hundreds of unidentified migrants in Falfurrias, Texas. Thanks to Canales's actions, many families came to know the fate of their loved ones.

PHOTO CREDIT: Jen Reel / Texas Observer

Adopt the soberanes station

-

Adopted by the Perry Sisters - Thank You!

This high desertlands water station is named after José Luis Soberanes, president of Mexico's Human Right Commission from 1999 to 2009. In 2005, the Mexican government reported that 441 of its citizens had died trying to cross the U.S. border, most of them in Arizona. The following year, Soberanes partnered with Humane Borders to distribute 70,000 warning maps at migrant staging points throughout Mexico.

Illustrated in Spanish, the posters warn migrants in stark terms about the dangers that lie on the journey north as represented by hundreds of red dots showing the locations of recovered human remains. The maps feature concentric circles representing how far a person can walk through the desert in one, two, or three days, and a chart of deaths by the month in which they occurred, emphasizing the increased danger of attempting to cross during scorching summer months. The posters strongly advise migrants to stay home: “No Vaya Ud! (Don’t go!) No Hay Suficiente Agua! (There isn’t enough water!) No Vale La Pena! (It’s not worth the risk!).

In 2020, Humane Borders revised the language on our warning maps to read as follows: Muchas personas han muerto cruzando (Many people have died crossing). No hay suficiente agua. (There isn't enough water). Muchas personas se pierden en el vasto desierto. (Many people have been lost in the vast desert).

Pictured: Jeannie Perry Wilfley Photo Credit: Mary Garcia

Adopt the luis and cindy urrea station

-

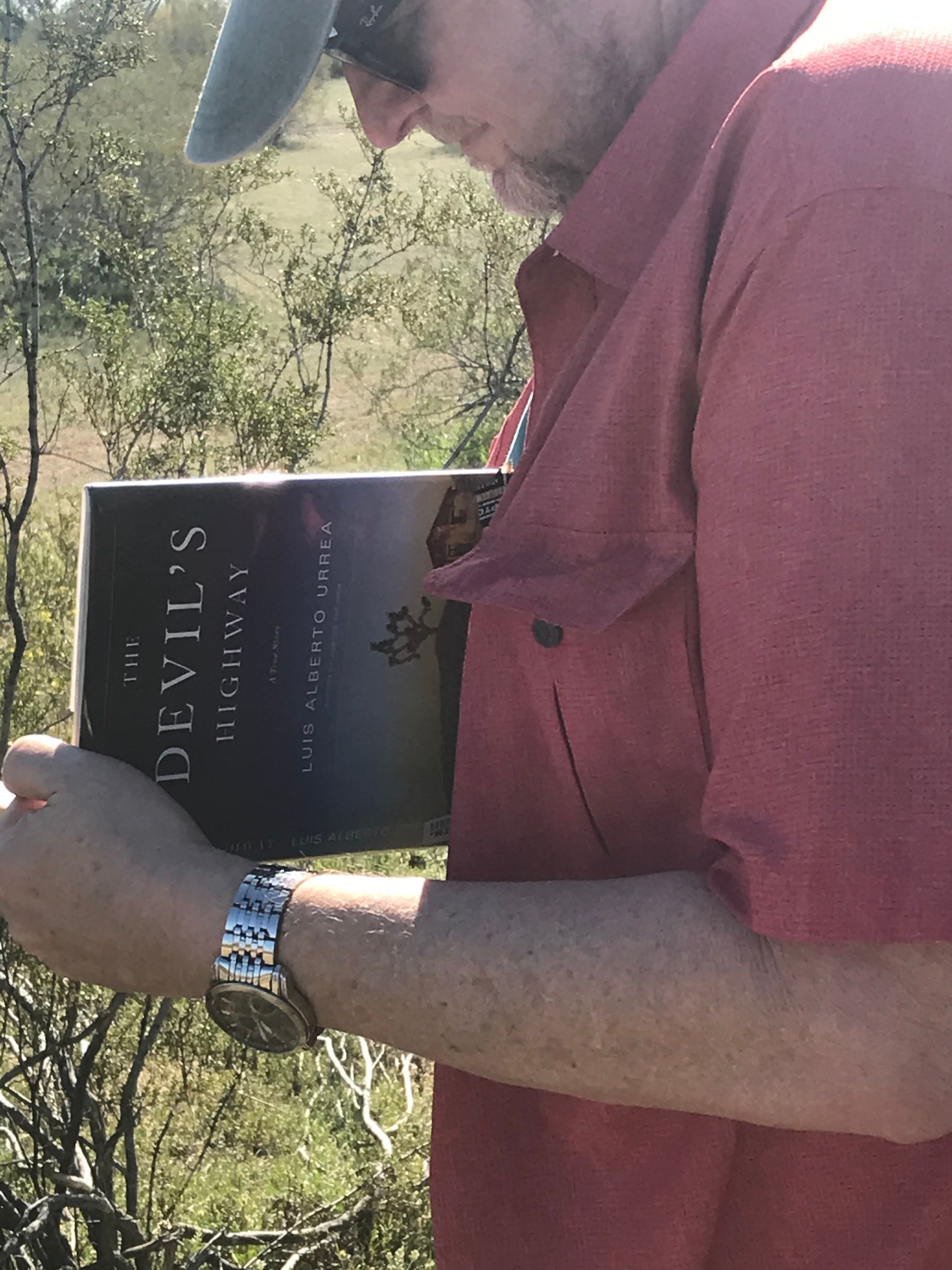

ADOPTED BY ANONYMOUS - THANK YOU!

This far-flung westerly station, dedicated to the work of Luis and Cindy Urrea, is situated off of the Camino del Diablo in Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge. The road is on the National Register of Historic Places and runs through the vast desert expanses of Cabeza Prieta, the Barry Goldwater bombing range, and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Starkly beautiful, the area provides scant shade from soaring temperatures that reach as high as 120 during summer months between May and October.

Alberto Urrea's acclaimed work, The Devil's Highway, relates the 2001 story of 14 migrants from Veracruz, Mexico who died after running out of water wandering lost in the desert for five days. It was the largest number of deaths in a single incident on record since 1980, when fourteen of twenty-six Salvadorans fleeing civil war in their country died after their smuggler left them without water in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, an area lying just twenty some odd miles to the west of Cabeza Prieta. Just a month before the tragedy, Humane Borders had sought but was denied permission to maintain water stations in the area.

Adopt the Green Valley Station

-

Adopted by Meg & Tim Dornfeld - Thank You!

Green Valley Station is one of a group of stations we service on our Arivaca water run. Our most easterly station, it is situated on private property near a pecan grove on the banks of the Santa Cruz. Green Valley Station is also our most urban station, but surprisingly sees a great degree of migrant activity. The area is also home to a good number of whitetail and mule deer. According to one longtime volunteer, it is seldom that volunteers don't see a dozen or more deer when servicing the station.

Adopt The Gurupreet KaUR Station

-

Adopted by Anonymous - thank you!

This special Organ Pipe station is dedicated to the memory of six-year old Gurupreet Kaur. On June 12, 2019, migrant traffickers led Gurupreet, her mother, and three other Indian nationals across the border into a very remote area west of Lukeville, AZ, leaving them there. Very quickly the situation grew dire as the heat reached 108 degrees. The group decided that Gurupreet's mom and a second woman should go find help, but the five would never reunite. Later that same day, Gurupreet died of heat stroke. Border patrol agents found her body just 22 hours after the grouped crossed the border into the U.S.

Like so many other asylum seekers, Gurupreet's parents were seeking a safer and better life for their daughter. They made an extremely hard decision that so many of us living out our comfortable lives in the U.S. will never have to make. In a statement released by the nonprofit Sikh Coalition, Gurupreet's parents said, “We trust that every parent, regardless of origin, color or creed, will understand that no mother or father ever puts their child in harm’s way unless they are desperate.”

Adopt The Sister Elizabeth Station

-

Adopted by Vauna Pipal - thank you!

This water station is named after Sister Elizabeth, or Sister Kizzie, to those who knew her best. Sister Kizzie, now passed, was beloved by everyone who knew her and has gone down as a legend in the Tucson border community. One of the founders of Humane Borders, she met with other concerned members of the Tucson faith community in 2000 to address what should be done about the growing number of migrant deaths in the Arizona Sonoran Desert. It was decided that life-saving water supplies should be placed at strategic sites where migrants were dying in the desert, and Humane Borders was born. As her obituary reads, "Whether dealing with Border Patrol, judges, immigration officials, or critics of [Humane Borders], she spoke with confidence and strength. In 2010, Humane Borders recognized Sister Elizabeth as Volunteer of the Decade.

Adopt The Hummingbird Station

-

Adopted by the McIntyre Boys

This remote water station is situated in rough and rocky terrain on the edge of Brawley Wash, between Pima County land and the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge where migrants are known to cross.

Hummingbird Station is dedicated to a long-time beloved volunteer, now passed, who was active in the Tucson border community for more than 20 years, and who served as a bridge and liaison between different Tucson desert humanitarian organizations. She will never be forgotten.

PHOTO CREDIT: Osha Gray Davidson

Adopt the Rocky Road Station

-

Adopted by A Friend of Penny Whiteford Pass from San Jose - thank you!

At one time, the road to Rocky Road Station was very difficult to traverse as the road we had to take to get there was made up of good-sized rocks. It was more of a big stone wash than a road! Today, during dry season, it's easier to drive as most of the larger rocks have been removed and the road is less bumpy. The image that you see here is taken from our water station, facing south towards "Rocky Road."

Unfortunately, because the road has become easier to navigate, Rocky Road Station has also become more vulnerable to vandals. Two or three times a year we will come upon the flagpole and water barrels destroyed. We waste no time rebuilding the station to ensure that precious water is available to migrants crossing.

PHOTO CREDIT: Stephen Lee Saltonstall

Adopt the Reyes-Carillo Station

-

Adopted by the Zelenda Foundation - Thank You!

The Reyes-Carillo Station is dedicated to a young woman immigrant from Guatemala. In the 1980s, Mima Reyes fled the land of her birth amid the violence of U.S.-backed dirty wars that plagued her country. Mima's journey crossing the border into the U.S. was a long, painful ordeal, but once in the U.S., with the help of a generous benefactor and an immigration attorney, she was able to get the proper documentation.

Mima will always hold a special place in the heart of Vice-Chair Bob Feinman. Mima cared for Bob's terminally ill mother, staying with her until the time of her death, going on to care for his aging father. In 2009, Humane Borders dedicated this water station to Mima and the Reyes-Carillo family.

Adopt the cemetery hill station

-

Adopted by Norman Gennaro - thank you!

Cemetery Hill, near Arivaca, is the site of an old homestead cemetery from the early 1900s. It's also one of the most challenging areas that we drive, involving an incredibly steep climb up and down a 4WD road that's been plagued by erosion over the years.

From the top of Cemetery Hill is a panoramic view of the Altar Valley, though the beauty belies just how dangerous this area is for people crossing.

Humane Borders driver Kirk Astroth penned a poignant essay about Cemetery Hill that describes the area and his thoughts about the important role Humane Borders plays in working to prevent migrant deaths.

adopt the Bishop Carcaño station

-

ADOPTED BY LAURIE PIEPER - THANK YOU!

North of the Arizona/Mexico border near the Sasabe Highway (286), this station prevents migrant deaths from dehydration. It also helps reduce the risk of people drinking unsafe water from cattle tanks at Altar Valley ranches.

In 2007, the station was dedicated to honor Bishop Minerva Carcaño, the first Hispanic woman appointed as a district superintendent of the United Methodist Church in the U.S., and the first Hispanic female elected bishop. Bishop Carcaño is well known for her commitment to ministering immigrants and refugees on the U.S./Mexico border.

Under Carcaño’s leadership, the United Methodist Church Relief Fund (UMCOR) granted Humane Borders funds for the purchase of two water trucks to service locations in the Arizona Sonoran Desert.

Humane Borders honors Bishop Carcaño’s advocacy efforts for the untold number of thirsty migrants crossing dangerous desert lands in search of life and hope.

adopt the tim holt station

-

adopted by deirdre roney and john cadarette - thank you!

Located between two washes, the Tim Holt station provides water in a remote area of the Ironwood National Monument about 70 miles north of the border. The area is graced by several species of hardy desert plants, including saguaro cactus, ocotillos, ironwoods, palo verdes, and chollas.

The station is named for longtime Humane Borders volunteer and treasurer Tim Holt, who is credited with rescuing a migrant woman he found near death near one of our stations. Holt called Border Patrol and cooled the woman while awaiting the arrival of a rescue helicopter, an action that likely saved her life.

In an interview after the event, Holt said, "The general public has no idea what's going on and they need to know." His compassionate action embodies what Humane Borders is all about.

Adopt the ed McCullough Station

-

Adopted by Dale and Leanna Rublaitus- Thank you!

Established on Pima County property, the Ed McCullough Station is situated on the fringe of the Ironwood National Monument in hauntingly beautiful but desolate mountainous desert terrain.

The McCullough Station is one of a special group of stations named after the people who are all about the heart and soul of the work that we are here to do: saving lives. Starting in 2002, Ed McCullough started producing maps in a project that would encompass more than six years of walking migrant trails and hundreds of hours of meticulously mapping nearly 4,000 miles of migrant trails on GPS systems.

McCullough’s work has contributed to the work that we do at Humane Borders as reflected by the stark red dots found on our death maps. From 2003 to 2018, McCullough worked in partnership with the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office to map the GPS coordinates where recovered human remains were found.

adopt the gene buell station

-

Adopted by Dr. Raul Rodriguez - thank you!

Our Gene Buell Station was named after a dedicated Humane Borders driver who took trips out for us for more than 15 years. For nearly 40 years, Gene led an interesting career as a geologist, and was stationed for some years at the bottom of the Grand Canyon. He loved spending time in this part of the desert where migrants were known to cross. It was Gene who came up with the idea for our cinderblock and wood barrel stands.

Gene Buell is one of three water stations that we maintain on Ironwood Monument lands, but unlike the other two Ironwood stations we service, Gene Buell is a lonely station situated on a vast floodplain where, as our Operations Manager Joel Smith so aptly puts it, "You can see forever." Standing at the station, volunteers can glimpse Baboquivari Peak to the south and Picacho Peak to the north.

Adopt Whispering Coyote Station

-

Adopted by Anonymous - thank you!

Whispering Coyote is one of seven water stations we maintain on City of Tucson lands where migrants cross. The station gets its name from an incident that occurred at the site on a water run back in 2019. Peculiarly, as the volunteers were checking the station's water levels, Truck 5 suddenly locked her own doors. Because there was a problem with the truck that necessitated leaving the engine running, the driver and volunteers were locked fast out.

After calling Triple A, the driver and a volunteer walked to the paved road to wait for the truck to arrive. As they stood, a large dog from a nearby property noticed them and was rapidly approaching. Suddenly, a coyote was heard in the distance. The moment was suspended in time as the three stood still listening, the two volunteers from their positions, the dog from a good hundred yards away as the coyote let out a long, mournful wail. The dog turned tail and ran after the coyote, allowing one of the volunteers who was fearful of the dog a safe exit back to the truck.

adopt the ross mine station

-

Adopted by Sandi and Jenn - thank you!

True to its name, the Ross Mine station is near a long-abandoned mine in southern Arizona near Arivaca. This station is located in a lush riparian area of the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge, and is one of the more challenging stations to access, with mud, deep ruts, and low-hanging trees all putting our drivers to the test.

The site is next to a wash that has served as a migration route over the years through hostile terrain and thornscrub.

The rosary shown here was hung in a tree by a Humane Borders volunteer who hoped it would serve as a source of comfort and inspiration for those on their long journey.

ADOPT the Silver bell Station

-

Adopted by Disciples Women's Ministries (DWM) - thank you!

This is one of three stations that Humane Borders maintains in the Ironwood Forest National Monument northwest of Tucson. Situated near the Silver Bell and Waterman Mountains, the monument encompasses nearly 300 square miles of Sonoran Desert. Carbon dating suggests some of the ironwood trees have survived more than 800 years.

Our Ironwood water stations are situated in some of the most beautiful landscapes in Southern Arizona. But for crossing migrants, this rugged, desolate landscape is harsh and unforgiving. Since 1991, 153 migrants have perished in this area. This is why Humane Borders is committed to maintaining its stations here--to prevent more migrant deaths.

adopt the figueroa Station

-

Adopted by The Straus Family - Thank You!

The Figueroa water station is in an elevated section of the Altar Valley, north of Arivaca. At the end of a dirt road, access to Figueroa can be tricky, requiring a steady climb while in 4 WD up a rocky road that winds through a grove of desert ocotillo.

During the summer rains, drivers must navigate around a large mud puddle that collects on a low section of road. There is a beautiful view of Baboquivari Peak from this station, though the beauty belies the sad reality that this area is among the deadliest for migrants in southern Arizona.

ADOPT THE DRIPPING SPRINGS STATION

-

ADOPTED BY CAROLE DAUGHTON - THANK YOU!

The Dripping Springs station lies near an outcrop of rough desert stone in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument near Lukeville, Arizona. The entire area looks ancient and volcanic, including the tall mountain immediately to the southwest. To the west, this dark, stony land falls away to a vast desert valley that appears endless. It must feel endless for someone trying to cross it. In spite of its name, the Humane Borders barrel is the only consistent water source at Dripping Springs, a scenic but deadly area.

ADOPT THE senita basin Station

-

ADOPTED BY THE STRAUS FAMILY - THANK YOU!

Our Senita Basin station is in a basin or depression in the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument near Lukeville, Arizona. The small basin is filled with organ pipe and senita cactus, as well as a myriad of other native desert plants. The senita cacti are long and armless and sometimes have "hair" or "beards" on their tips.

On one water run, we found a black one-gallon water jug under the spigot of the barrel. We felt certain our arrival had interrupted someone getting water. We left the jug behind so this person could resume filling it and continue on their journey. Now, every time we visit the station, we wonder what happened to the traveler who left the jug behind.

ADOPT THE RED TANKS STATION

-

ADOPTED BY THE STRAUS FAMILY - THANK YOU!

The Red Tanks station is near the loop drive through Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument near Lukeville, Arizona. Since there are no vehicles allowed off the main road, we hike on foot with a long drinking-water-safe hose to replenish our barrel, traveling across a wash and around a fallen ocotillo.

Hikers and tourists often see the Humane Borders water truck and are curious about what we're doing, stopping to talk with us. Everyone we've encountered is supportive of our mission and one person gave us a cash donation on the spot. Our water is for everyone!

ADOPT THE kim johnson STATION

-

Adopted by the Johnson Family - Thank you! in Memory of Our Beloved Sister

Named in memory of the beloved Humane Borders volunteer pictured here, the Kim Johnson water station is in the Altar Valley off the Sasabe Highway (286). This is an area where, sadly, many people have died over the years, in the shadow of the Baboquivari Mountains.

To access the station requires maneuvering through a dense grove of thorny trees (which leave "Arizona pinstripes" on the sides of our vehicles), and around a large mudhole that forms after it rains. This station is also known for a large sandpit on approach to the barrel, that can present a challenge for even the most experienced drivers. We're committed to bringing water to the desert even under these challenging conditions.

adopt the GUADALUPE station

-

ADOPTED BY THE STRAUS FAMILY - THANK YOU!

The Guadalupe water station is in a remote area of the Sonoran Desert northeast of Tucson. While it's owned by the City of Tucson, it's a far cry from the city.

This station is on what we call City of Tucson water run, which can be challenging in the summer after monsoon rains. Vegetation can grow so high it makes route-finding difficult, so our experienced drivers rely on GPS recordings to find their way.

Here, a member of a student group fills the barrel as other students look on. We love our student volunteers!

Adopt The K-9 Station

-

Adopted by the Straus Family - thank you!

Our K-9 Water Station is one of six stations on our Arivaca water run. It was originally named after a ranch in the area where dogs were raised. Humane Borders established the station at the site after discovering that migrants were getting sick filling their bottles with the green bacteria-laden water from a cattle tank located just north of the station. Because the station is in a flat area that is easily accessible to most vehicles, we also use K-9 for educational purposes. Humane Borders volunteers have taken many student, church, and other organizational trips to this station to raise awareness on the plight of so many migrants dying for lack of water in the desert.

WITH CARLOS ESPINA

PHOTO CREDIT: LAURIE CANTILLO

Adopt the poplar grove station

-

ADOPTED BY KANYA IWANA - THANK YOU!

Poplar Grove, one of the water stations we service on our City of Tucson run, was named by a former volunteer who mistakenly thought that some 30-odd trees on site were poplar trees. In fact, they're eucalyptus trees, but the name stuck. The station is shaded under a small clump of trees in a flat area that was cleared for ranching and farming several decades ago, and where migrants still cross.

A large open area nearby is home to caracara raptors, a large bird of prey belonging to the falcon family. Nearby, on top one of the hills that we drive past, lies a Hohokam village ruins, and volunteers have often discovered pottery shards in the area.

how to adopt a water station

Interested in adopting a Humane Borders water station? Please click the blue "Adopt Now" button below. Put in the "public message of support" that your $1,000 donation is for "ADOPT A STATION." Include which station you want to adopt and check the box if you want the donation to be anonymous. That's it!

Other ways you support our lifesaving work:

$500 - BLUE FLAGS FOREVER

$250 - WATER BEARER

$100 - BUY A BARREL

$50 - GAS BUDDY

~thank you for caring~