From the Arizona Daily Star investigation: Death in the desert series

Curt Prendergast , Alex Devoid | Dec 2, 2021 Updated Dec 3, 2021

First of four stories

Opposing principles

‘For my family’

Crossing the wilderness

Shaky correlation

Longer, more perilous routes

Already exhausted upon reaching US

‘Funnel effects’

Body count is up in unwalled areas

Repeat crossings follow expulsions

Planting crosses

Second of four stories

Despite their best efforts, they had arrived too late. Guillermo died, just a week after he turned 23.

Calls for help come from migrants stranded in mountain ranges, such as the Baboquivari Mountains southwest of Tucson where trails rise up steep mountainsides and crisscross ridges. Migrants call when they are lost in the desert dozens of miles from the nearest signs of civilization. Calls also come from family members desperate to know what happened to loved ones who went missing after crossing the border.

Those calls spur Border Patrol agents, paramedics and sheriff’s deputies to hustle down remote roads or fly helicopters along mountainsides. The calls prompt humanitarian aid volunteers from groups like Tucson-based No More Deaths to coordinate between family members and first responders.

Rescuing migrants in the desert requires overcoming a multitude of challenges, the Arizona Daily Star found by analyzing incident reports from sheriff’s departments and other local law enforcement agencies, audio recordings of 911 calls, and data from medical examiners in Pima and Yuma counties.

Some calls came before medical help was needed, but others came just minutes before the caller or their companions succumbed to heat and dehydration.

“I need help. My friend is dying. Hurry! Hurry!” one man said in a call from the Altar Valley north of Sasabe. “He’s not drinking water anymore.”

“Please, help. I’m alone. They left me,” a man said through tears in a call from east of Arivaca.

“My chest hurts, my heart,” the man said when the 911 dispatcher asked him if he was injured.

“We’re lost in the desert. Can you help us? I can’t take it anymore,” a man said in a call from the Three Points area.

“I don’t have anything left to eat. I don’t have any water. I feel like I’m going to pass out,” a woman said in a call that pinged off a cellphone tower near Green Valley.

Some areas have spotty reception, leading to frequent dropped calls as 911 dispatchers and Border Patrol agents try to gather information from the migrant in distress. In other, huge areas of the desert west of Tucson, there is no cellphone coverage, making calls for help impossible.

The wilderness in Southern Arizona is as large as several states, and would-be rescuers often have little information about where distress calls come from. When they have an exact location, they may still have to travel long distances over rough terrain to make the rescue.

Rescue efforts unfold across 20 jurisdictions that include local sheriff’s departments, U.S. Fish and Wildlife officers, National Park Service rangers, and the Tohono O’odham Nation Police Department. When calls come from areas that could be in multiple jurisdictions, 911 dispatchers have to figure out where to refer the call.

The de facto situation is that the Border Patrol has dual roles as the main enforcer of immigration laws and the main responder to migrants in distress. At the same time, search-and-rescue efforts technically are the responsibility of county officials, not the Border Patrol.

Either way, local law enforcement agencies and the Border Patrol have limited resources to respond to these distress calls.

Humanitarian aid volunteers see saving migrants as their top priority, but they do not have the authority to take effective action. Their efforts are hemmed in by federal agencies like the Border Patrol and the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

The speed and effectiveness of rescues have become even more important over the last two years as more migrants were found shortly after their deaths.

Just in June, the bodies of 16 migrants were found within 24 hours of their deaths, the highest monthly total in at least a decade and more than all such cases reported in 2019. Another 13 sets of remains were found within one week, also the highest monthly total in at least a decade, according to Pima County’s medical examiner. More than 1,000 sets of remains have been found within one day of death since 2000.

Rescues are not keeping pace.

The Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector reported rescuing 14 migrants in need of medical care from May to July. During those months, the remains of 126 migrants were found, including 35 who were found within a day of death and 25 within a week of death.

If rescue efforts were to increase, they would not necessarily have to be spread across the length and breadth of Southern Arizona, the Star’s geographical analysis of medical examiner data shows. Instead, they could focus on certain cross-border corridors that are the deadliest for migrants. Even within those corridors, large numbers of deaths occur in very specific areas.

Difficult rescues

Local officials sometimes lack the resources to conduct simultaneous searches.

In the case of Jeremias Soto Velazquez, all would-be rescuers knew was that he was last seen near a water tank somewhere south of Little Tucson on the Tohono O’odham Nation reservation.

A Guatemalan man stranded in the Baboquivari Mountains southwest of Tucson is lifted into a helicopter by Border Patrol rescuers in late July. U.S. Customs and Border Protection

Soto crossed the border with a group of migrants in May 2020, but he grew ill and eventually fell unconscious. The group left him on the west side of the Baboquivari Mountains. A family member called a hotline run by No More Deaths, who then called the Tohono O’odham Nation Police Department, says an incident report from the tribal police.

But the Tohono O’odham police were busy searching for another missing person elsewhere on the reservation. The next day, Soto’s father told No More Deaths volunteers that Soto was left by a water tank or well, but he didn’t have Soto’s precise location. The report does not say how Soto’s father learned that information.

Again, the Police Department did not have any resources available. It wasn’t until three days after Soto went missing that those resources became available and police searched for him. They couldn’t find him.

The search effort was given a boost after a man in Soto’s group returned to where they had left him and brought him water. The man logged the GPS coordinates for Soto’s location and passed them to Border Patrol agents when they picked him up. Using those coordinates, a police officer found Soto’s body.

In other instances, rescue efforts get tangled up in jurisdictional confusion that costs precious minutes.

On May 6, 2021, two cousins crossed the border southwest of Tucson. They made it all the way to an area west of Marana, but one started to feel sick and the other called 911, according to an incident report from the Pima County Sheriff’s Department. Deputies from Pima and Pinal counties, along with officers from the Tohono O’odham Nation Police Department, tried to figure out who had jurisdiction.

A half hour went by and one cousin called 911 again to say the other had stopped breathing. A short time later, Borstar (Border Patrol Search, Trauma and Rescue) agents arrived and tried to treat the cousin, but he had died.

In some cases, humanitarian groups and relatives of a missing migrant must step in when official efforts fail.

During a record-breaking series of 100-degree days in June, four brothers showed up at the Pima County Sheriff’s Department to ask about their brother-in-law. He had gone missing after crossing the border through the desert southwest of Tucson.

Their brother-in-law, Carlos Arevalo Gonzalez, crossed the border on June 12 near Sasabe. Border Patrol agents caught the group two days later south of Three Points, about 30 miles southwest of Tucson, but by that time a woman in the group had died, a sheriff’s deputy wrote in an incident report.

The Mexican Consulate had informed the brothers that the woman who died, Berta Ladios, was in the group that crossed the border with their brother-in-law. One of the migrants in the group contacted the brothers and told them Arevalo was not doing well after they left Ladios behind when she died. Soon after, the group left Arevalo.

Deputies searched for Arevalo, but couldn’t find him. One of the brothers told a deputy that he and volunteers with No More Deaths would search the next day. They followed birds to Arevalo’s body, about 30 miles north of the border.

Calling for help

When officials spoke to a crowd of news reporters this spring for an annual border safety event, they tried to send a clear message to any migrants planning to cross the border: Call 911 if you need help. Don’t waste precious battery calling your family or anyone else.

Inside a hangar filled with airplanes and helicopters used to rescue migrants at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, officials from the Border Patrol, Mexican consulate and Guatemalan consulate took turns driving home the message, meant to take advantage of the fact that many migrants carry cellphones when they cross the border.

Deputy Chief Patrol Agent Sabri Dikman urged migrants not to cross the border illegally, saying, “Don’t do it. The desert is vast and treacherous.”

“To find a person whose only location information is, ‘I’ve been walking for five days’ can be nearly impossible,” Dikman said. “Even with our best resources, the task can take days.”

For migrants who carry a phone, he urged them to call 911: “This is your single best chance for being rescued.”

The southern foothills of the Baboquivari Mountains west of Sasabe. “The desert is vast and treacherous,” the Border Patrol’s Sabri Dikman warns migrants contemplating a crossing. “Don’t do it.” Josh Galemore photos, Arizona Daily Star

“If you call anyone else, you’re wasting your battery. That cellphone battery is your life. Call 911,” Dikman said.

Ideally, rescuers would then be able to locate migrants using cellphone towers. In a positive development for rescue efforts, 911 is also now the emergency number in the Mexican state of Sonora, just south of Arizona.

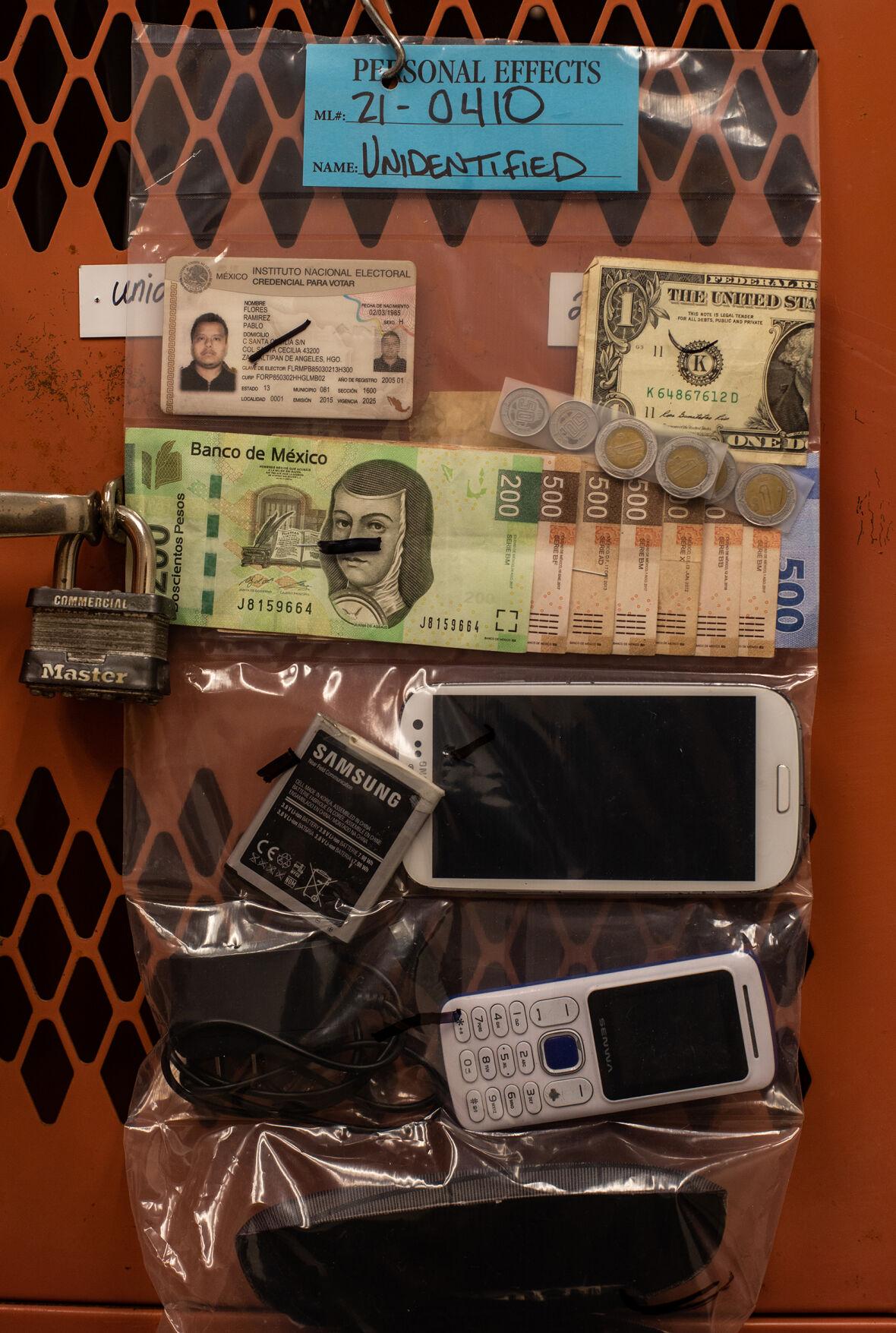

Yet, at the Medical Examiner’s Office in Tucson, many of the bags containing property recovered at the scene of a death include at least one cellphone. Incident reports from local law enforcement agencies often mention finding phones and solar battery chargers next to migrants who died in the desert.

While Border Patrol agents, local law enforcement and humanitarian volunteers can respond to hundreds of 911 calls every year, those efforts face an obstacle that no amount of individual effort can overcome: They can’t respond to distress calls that are never made.

The desert west of Tucson has been one of the busiest areas for border crossings for many years, but vast areas of it either do not have cell coverage of any kind or the coverage is spotty and unreliable, according to coverage maps from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission as of June 2020.

The largest coverage hole is in and around the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, one of the deadliest areas for migrants in Southern Arizona. Smaller holes dot the mountain ranges that run north-south across the border.

The remains of 48 migrants were found in areas without cell coverage since the start of 2021. Another 66 sets of remains were found in those areas in 2020, the Star found by comparing data on migrant deaths with cellphone coverage maps from the FCC. The remains of 514 migrants were found in those areas since 2000.

Nearly all the 911 calls the Star reviewed came from the area between Nogales and the eastern portion of the Tohono O’odham Nation reservation.

The only calls from west of the reservation came from humanitarians, ranchers or wildlife officials reporting the discovery of human remains.

Nerve center

The limits created by the lack of cell coverage are clearly visible inside an office on South Swan Road that the Border Patrol uses as its nerve center for rescuing migrants.

A massive 30-foot-long screen dominates one wall, while agents sit in rows of cubicles with phones pressed to their ears. The screen shows a map of Southern Arizona, similar to the topographical maps offered by Google Maps, with icons showing where distress calls came from and how far agents are from arriving at the migrant’s location.

The map showed three red icons of telephones on June 17, indicating three distress calls from migrants in the Baboquivari Mountains. Icons for Border Patrol agents slowly moved across the screen toward them.

The area from the New Mexico state line to the Tohono O’odham Nation reservation was abuzz with icons showing migrants, agents, aircraft and other Border Patrol assets. But much of the desert west of Ajo showed no activity at all.

The Border Patrol’s wall-sized video screen at the Arizona Air Coordination Center shows the location of rescue call stations and active rescues in the Tucson Sector. Curt Prendergast, Arizona Daily Star

The lack of cell coverage west of Ajo is a fact that Agent Ryan Riccucci, who leads the rescue efforts from the office, must work around. Simply put: “People can’t call for help out in that area,” he said.

Even for migrants who are in areas with cellphone reception, the ability to make a call does not guarantee a rescue.

Migrants at a shelter in Nogales, Sonora, said smugglers told them not to turn on their phones because the Border Patrol would be able to track the signal; or that they bought a phone to be able to make calls, but the signal was unreliable.

Calls to the 911 dispatch center at the Pima County Sheriff’s Department often were dropped repeatedly, much to the frustration of dispatchers, Border Patrol agents and migrants, the Star found after reviewing roughly 150 calls the Sheriff’s Department transferred to the Border Patrol since September 2020.

Deadliest areas

The border counties in Arizona where migrants cross into the U.S. include about 27,500 square miles, or more than three times the size of El Salvador.

But migrant deaths are not spread evenly across that area. Instead, remains are found in a small fraction of it, focused on specific areas west of Tucson, a geographical analysis by the Star shows.

Every year since 2000, at least 50% of the remains were found in less than 8% of those 27,500 square miles; in some years it was as little as 3% of that area.

The concentration of deaths in certain areas could allow more focused rescue efforts to be more successful.

The Star divided Southern Arizona into sections that cover 100 square miles each, and found that deaths tend to cluster in some of the areas. For example, about 50% of all remains found in 2021 were in 16 of these areas, which add up to about 6% of the area in border counties.

Nearly all of these 16 areas are west of Interstate 19. Most overlap the Tohono O’odham Nation reservation. Others overlap the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range and a section of the Coronado National Forest along the border. East of Interstate 19, one area overlaps the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area.

Using the 12 cross-border corridors established by the aid group Humane Borders, the Star found the corridor west of the Baboquivari Mountains is the deadliest one in 2021, with more than triple the death count of any other corridor.

Within that corridor, many of the deaths are concentrated in smaller areas. A cluster of seven of these areas near Sells, on the Tohono O’odham Nation, accounted for 25% of all deaths in border counties so far in 2021. These seven areas account for less than 3% of the area across Arizona’s border counties.

Small measures

As they have done for two decades, local aid groups and the Border Patrol push forward small-scale measures on their own initiatives.

The Border Patrol increased its rescue efforts over the years, although officials are quick to say they must balance efforts to rescue migrants with the agency’s primary goal of securing the border.

“Our primary mission is border security, but we are a link in the emergency management system,” Riccucci said. When agents get a distress call from a 911 dispatch center, “at that moment the border security mission stops and it becomes purely humanitarian,” he said.

The Border Patrol now has an integrated system to relay information about migrants in distress between the Tucson headquarters and agents on the ground and in the air, which Riccucci said has allowed them to respond to twice as many distress calls.

The Tucson Sector’s 3,600 agents now include 23 paramedics, 53 Borstar agents, who are specially trained in search and rescue, and more than 230 agents trained as emergency medical technicians.

The Border Patrol set up more than 30 rescue beacons, which have a blue light to make them visible at night. Migrants in distress can push a button on the beacon to alert the Border Patrol that they need help.

Migrants in distress can push a button on one of more than 30 rescue beacons set up by the Border Patrol, but the effectiveness of the beacons remains unclear. Josh Galemore, Arizona Daily Star

The Border Patrol also placed a half-dozen satellite phones in the desert, akin to roadside assistance phones, and 30 placards migrants can use as reference points when calling 911.

The effectiveness of the rescue beacons is unclear. Tucson Sector officials did not provide data on their use to the Star. The best available data came from a Customs and Border Protection report in February, which said 144 rescues were associated with 67 rescue beacons “in the southwestern section of Arizona” in fiscal 2019.

“At this time, CBP’s data systems lack the interoperability and data sets that would enable CBP to track and share specific information associated with migrant rescues with federal, state, and local partners, rescue beacons, 911 placards, location and identification of remains, and cellphone coverage on a large-scale basis,” CBP officials said in the report.

A network of humanitarian groups focused on rescues sprang up in Southern Arizona since the early 2000s.

Some areas of the desert in Southern Arizona are now dotted with blue water barrels, maintained by Humane Borders, and small caches of water jugs and food placed on migrant trails by volunteers with No More Deaths, which also runs a camp for migrants in need of medical care near Arivaca, much to the aggravation of Border Patrol officials.

Groups such as Border Angels, Aguilas del Desierto (Eagles of the Desert), Armadillos Busqueda and Rescate (Armadillos Search and Rescue), and Battalion Search and Rescue all search for remains in the desert.

La Coalicion de Derechos Humanos (The Coalition of Human Rights) established a crisis call center to help families find lost loved ones. The Border Patrol runs a similar operation to find missing migrants by coordinating family members, consulates and law enforcement agencies.

The Colibri Center for Human Rights helps families identify lost loved ones, at times by conducting DNA tests. Humane Borders used medical examiner data to build a public database on migrant deaths.

The efforts of these humanitarian groups unfold within tight boundaries built up over the years by federal officials in Arizona.

The Border Patrol and the U.S. Attorney’s Office repeatedly cracked down on humanitarian efforts they viewed as crossing the line between helping migrants and aiding human smuggling.

As far back as the 1980s, federal authorities arrested members of the Sanctuary Movement on human-smuggling charges after they offered shelter at churches in Tucson to refugees from Central America.

In the 2000s, as volunteer humanitarian efforts spread into the desert, a federal judge ruled that volunteers could not legally transport migrants in distress to hospitals in Tucson.

In recent years, Border Patrol agents entered No More Deaths’ medical camp near Arivaca without permission several times after surrounding the camp with agents and trucks.

Even leaving food and water on migrant trails could be a criminal offense. Fish and Wildlife officials changed regulations on the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge in the summer of 2017 to prohibit leaving food and water there. Nine No More Deaths volunteers faced federal misdemeanor charges when they disregarded that rule change, citing a humanitarian imperative to help migrants in distress.

The remains of more than 160 migrants were found on or near the Cabeza Prieta refuge since the summer of 2017.

In 2018, No More Deaths volunteer Scott Warren faced felony human-smuggling charges after he let a pair of migrants spend two nights at a No More Deaths aid station in Ajo.

Reminders of lives lost

One local effort that has become the gold standard along the U.S.-Mexico border is the record-keeping at the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner.

Over the course of 20 years, the office has built the capacity to quickly and accurately document migrant deaths, director Dr. Greg Hess said.

That effort is guided by the public’s interest in migrant deaths, similar to the public’s interest in deaths resulting from drug overdoses, suicides, firearms and other causes, he said.

“We try to keep as much detailed, objective information as we can to respond to people’s needs to learn about those different types of deaths,” Hess said.

The county medical examiner is not required by law to document the deaths of migrants, but it is a task that any civilized country should take on, Hess said.

“There isn’t anything that requires one to keep track of this group separately from all the other remains that are reported to you,” Hess said. “Legally, the only thing the law says one must do with unidentified remains is report it to the medical examiner’s office. That’s it.”

While Hess keeps the public up to date on deaths in the desert, lockers in a small room down the hall from his office fill up with heartbreaking reminders of the lives lost.

Belongings found on migrants who died in the deserts of Southern Arizona are kept in sealed bags at the Medical Examiner’s Office on Tucson’s south side. Josh Galemore, Arizona Daily Star

A wallet-sized photo of a little girl with one pigtail tied with a red scrunchie. A water-soaked Bible. Prayer cards and rosaries. A receipt for a refrigerator. School records. Marriage records. A business card for a Tucson immigration lawyer. Pages of handwritten phone numbers. Letters to loved ones.

“My love, I know we are not a perfect couple but I love you,” read a letter found among the property of one woman who died.

“I’ve always told you that you are the love of my life and you really are important in my life,” she wrote in Spanish. “I know that sometimes I’m not the woman that you wanted in your life and the truth is that I know you sometimes get bored with me for how I am. I love you and I thank you for staying by my side in spite of everything.”

Day after day, the remains of the people who carried those items and wrote those words are wrapped in white plastic sheets and placed in the cooler, waiting for their loved ones to claim them.

At an office on South Swan Road in Tucson, a Border Patrol agent talks to a group of five lost somewhere in the Baboquivari Mountains. The corridor west of that mountain range has triple the death count of any other area this year in Arizona’s borderlands. Kelly Presnell, Arizona Daily Star

Third of four stories

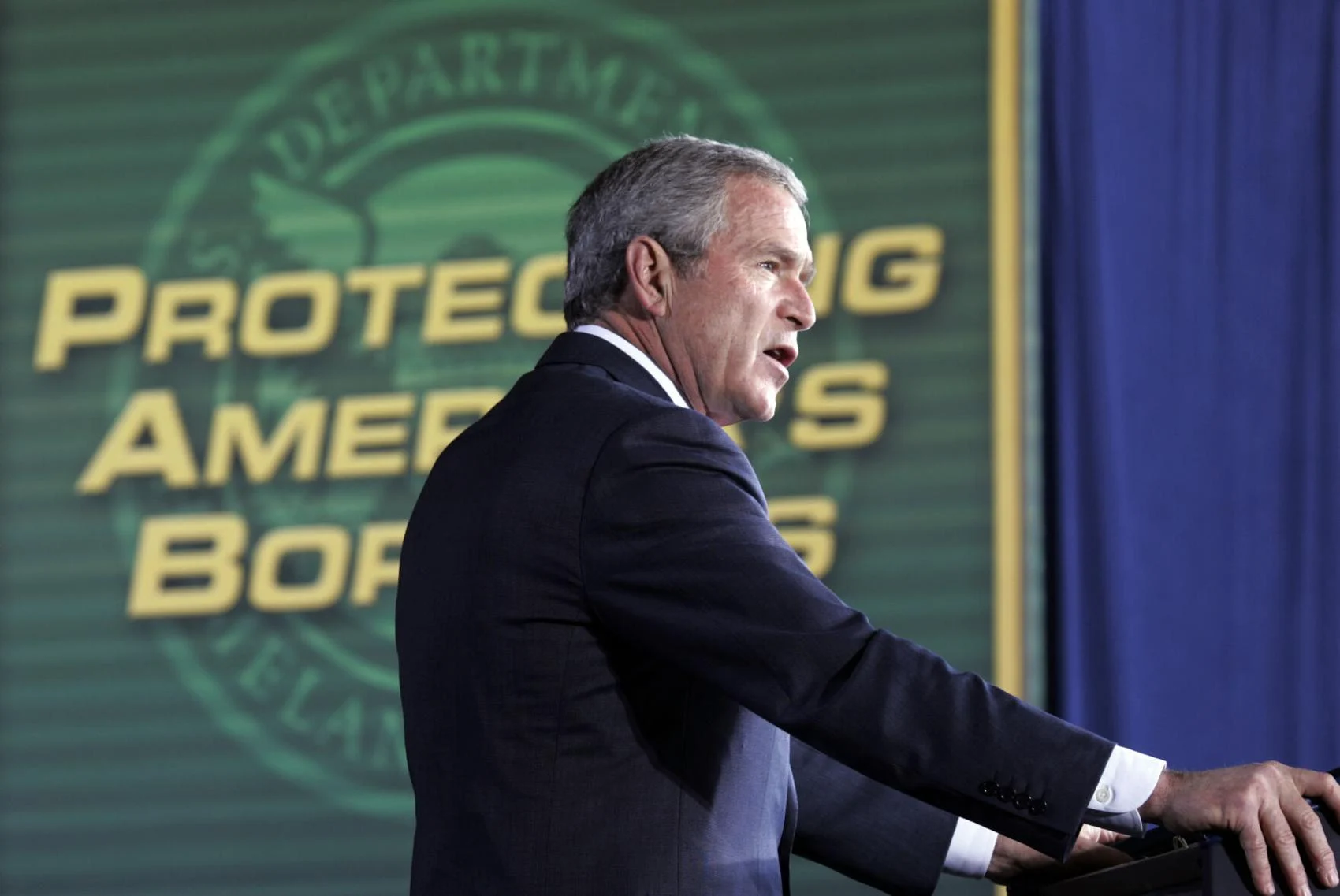

As a political issue, the deaths of thousands of migrants in Southern Arizona rarely appear at the forefront of federal lawmakers’ discussions.

The issue popped up sporadically over the past two decades in bills proposed by a handful of lawmakers from both the Republican and Democratic parties. In all but one instance, bills that addressed migrant deaths either stalled in committees or were voted down as part of comprehensive immigration reform bills, the Star found after reviewing Library of Congress archives since 2000.

Soaring rhetoric about a “higher moral obligation” to save lives in 2006 from Sen. Bill Frist, a Republican from Tennessee, faded away over the years. Migrant deaths remain part of the immigration debate, but they mainly are relegated to the periphery of that discussion unless they can be used as props for other arguments, the Star found by tracking 2021 comments from officials and lawmakers.

In March, President Biden tried inaccurately to explain away a dramatic rise in border crossings by saying migrants cross in the winter to avoid the deadly summer heat. Migrant deaths were the top reason Yuma County officials cited to justify Gov. Doug Ducey’s deployment of the National Guard to the border in April, despite the Guard’s mission not including rescues. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, a Democrat from Arizona, cited the deadly danger of crossing the border in Southern Arizona as a reason to support her immigration bill during a visit to Tucson in June, even though her bill did not address migrant deaths.

Large-scale deaths of migrants began in 2000 and continued regardless of whether the president was a Democrat or Republican. The remains of 500 to 800 migrants were found in Southern Arizona during each presidential term, including 1,400 during the two terms Joe Biden served as vice president during the Obama administration.

Since Biden’s first term as president began in January, the remains of more than 222 migrants were found in Southern Arizona, putting this year on pace to surpass the record-breaking 239 remains found in 2020. Biden has proposed wide-ranging reforms to immigration and border policy, but none is aimed at reducing migrant deaths.

In this 2003 photo, Tijuana artist Alberto Caro speaks at the U.S.-Mexico border fence in Tijuana, Mexico, at a ceremony marking the ninth anniversary of Operation Gatekeeper, a Border Patrol program that critics say forced illegal immigrants into crossing Arizona’s desert. A coffin marked with the number of immigrants who died trying to cross the border that year was hung next to coffins with previous years’ death totals. Lenny Ignelzi, Associated Press

‘We have higher moral obligation’

Immigration reform and border enforcement frequently appeared in federal legislation since 2000, but the vast majority of those bills did not address migrant deaths.

When lawmakers did address those deaths, the proposed measures made little progress, with certain provisions jumping from bill to bill over the years without becoming law.

In 2006, Frist introduced the Border Deaths Reduction Act, which would have directed Customs and Border Protection officials to gather data on the number of migrant deaths, causes of deaths, locations and demographic information.

If Congress had passed the bill, CBP officials would have analyzed trends in that data, evaluated CBP strategies for reducing migrant deaths, including the use of rescue beacons, and recommended actions to reduce those deaths.

The report in Frist’s bill would have contained “particular emphasis on enhancing the deployment of rescue beacons in the Tucson Sector.” The bill would have authorized $500,000 for the report and $1.5 million to deploy more rescue beacons.

No votes were held on the bill in the Senate.

When Frist introduced the bill, he pointed to a Government Accountability Office report that said migrant deaths had doubled since 1995, despite border crossings not increasing. The Border Patrol “has not addressed these limitations to sufficiently support its assertions about the effectiveness of some of its efforts to reduce border-crossing deaths,” GAO officials wrote.

The results of the GAO report were “sobering, shocking, and, I strongly believe, a cause for action,” Frist said as he introduced the bill in 2006. “Since 1995, deaths along our borders have doubled. Despite the heroic rescue efforts of the men and women of Customs and Border Protection, things have gotten worse.”

The increase in migrant deaths “stem largely from an increase in deaths from exposure to the elements in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona,” Frist said at the time. “Illegal entries, however, have not increased. Quite frankly, it is getting more dangerous to cross the border.”

“Until recently, CBP did not even keep a systematic count of those who died crossing our borders,” Frist said. “We still do not have a unified national strategy for reducing the deaths. We still do not know how well our safety efforts work — if they are saving lives or not. We need to do more.”

“The founding document of our nation, the Declaration of Independence, lists ‘life’ first on the list of the government’s responsibilities,” Frist said. “The overwhelming majority of the people who cross our border do so in search of a better life. They take enormous risks and make enormous investments in hopes of helping their families.”

“Illegal immigration needs to stop,” Frist said. “We must defend our borders. We must construct physical barriers, add detention beds, hire personnel and equip them with better technology.”

“But we have a higher moral obligation to protect the life of every person —every man, woman, and child — who sets foot on American soil. We must do everything in our power to preserve life,” Frist said.

At that point, the remains of about 1,040 migrants had been found in Southern Arizona, according to the Pima County medical examiner.

Although Frist’s bill did not become law, the provisions in the bill about gathering data on migrant deaths, compiling a report, and recommending actions to reduce those deaths were included in several comprehensive immigration reform bills introduced in 2006 by three other Republican senators: Arlen Specter from Pennsylvania, Chuck Hagel from Nebraska and Rick Santorum from Pennsylvania.

Specter’s bill passed the Senate, but not the House. The bills sponsored by Hagel and Santorum did not advance beyond the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The following year, the same provisions appeared in bills proposed by Sen. Edward Kennedy, a Democrat from Massachusetts, Rep. Luis Gutierrez, a Democrat from Illinois, Sen. Harry Reid, a Democrat from Nevada, and Sen. Johnny Isakson, a Republican from Georgia. None of the bills became law. Reid’s comprehensive immigration bill was widely debated in the Senate but ultimately did not pass.

The provisions expanded in 2009, when Rep. Solomon Ortiz, a Democrat from Texas, sponsored a bill that included directing CBP officials to “conduct a study of Southwest Border Enforcement operations since 1994 and its relationship to death rates on the US-Mexico border.”

President George W. Bush speaks about border security at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson in 2005. Ron Medvescek, Arizona Daily Star

Legislation lags as deaths mount

The study in Ortiz’s bill would have included an analysis of the “relationship of border enforcement and deaths on the border,” whether “physical barriers, technology and enforcement programs have contributed to the rate of migrant deaths,” and the “effectiveness of geographical terrain as a natural barrier for entry into the United States in achieving department goals and its role in contributing to rates of migrant deaths.”

The study also would have directed CBP officials to consult with nongovernmental organizations and community members “involved in recovering and identifying migrant deaths” and an “assessment of existing protocol related to reporting, tracking and inter-agency communications between CBP and local first responders and consular services.”

The report on the study would have been submitted to the “United States-Mexico Border Enforcement Commission,” made up of a mix of local and federal officials, border residents and others.

Ortiz’s bill was referred to committees and no vote was held in the House.

By the end of 2009, the remains of about 1,620 migrants had been found in Southern Arizona.

The expanded provision appeared again in 2010 in a bill sponsored by Sen. Robert Menendez, a Democratic senator from New Jersey who is helping lead the charge on Biden’s immigration bill in 2021. The expanded provision also appeared in 2012 in a bill from Rep. Raúl Grijalva, a Democrat who has represented districts along Arizona’s border with Mexico since 2003. Neither bill passed.

In 2013, Sen. Charles Schumer, a Democrat from New York and current majority leader, sponsored a comprehensive immigration bill that included provisions calling for CBP to identify areas where migrant deaths are the most frequent, study the relationship between enforcement and deaths, clarify CBP efforts to mitigate those deaths and install up to 1,000 rescue beacons.

By that point, the remains of about 2,400 migrants had been found in Southern Arizona.

In 2014, the Border Patrol changed how it counted migrant deaths to include only instances where an agent was directly involved. As a result, the Border Patrol’s count started to diverge dramatically from the count by the Pima County medical examiner. In 2020, the Border Patrol’s Tucson and Yuma sectors reported 49 migrant deaths, roughly one-fifth of the 239 counted by medical examiners in Arizona.

In 2014 and again in 2015 and 2017, a bill introduced by Rep. Beto O’Rourke, a Democrat from Texas, would have directed CBP to gather data on migrant deaths, including the extent to which CBP has “adopted simple and low-cost measures, such as water supply sites and rescue beacons, to reduce the frequency of migrants’ deaths.”

Grijalva introduced a bill in 2015 and again in 2017 that would have directed CBP to gather data, analyze trends, recommend actions, and study the relationship between enforcement and migrant deaths. The bill also would have directed CBP to specify where rescue beacons were needed.

In 2017, Sen. John Cornyn, a Republican from Texas, introduced a bill to direct CBP to figure out the total number of migrant deaths and report to Congress on efforts to identify remains.

By the end of 2017, the remains of about 2,950 migrants had been found in Southern Arizona.

In 2019, Rep. Veronica Escobar, a Democrat from El Paso, introduced the Homeland Security Improvement Act. That bill would have directed CBP officials to evaluate policies to “reduce the number of migrant deaths,” among other provisions. It also would have directed CBP to report the “extent to which border technology, physical barriers, and enforcement programs have contributed to such migrant deaths.”

Escobar’s bill passed the House, but not the Senate. During the debate on the House floor, Rep. Mike Rogers, a Republican from Alabama, opposed the bill on similar grounds to the current opposition to immigration reform.

“Law enforcement has encountered nearly a million migrants illegally crossing the southwest border,” Rogers said in September 2019. Democrats refused to see the “crisis,” he said, and after Trump administration policies took effect the “crisis has finally abated.”

Instead of proposing “another partisan messaging bill that stands no chance of becoming law,” Democrats should have presented a “bipartisan bill to address the causes of the border crisis and prevent another one from happening,” Rogers said.

In response, Escobar said the bill was an “opportunity to come together and begin to make a powerful and well-funded federal agency more accountable to the Congress and to the people that they serve.” The bill “comes right from the communities that are impacted the most,” Escobar said.

Rep. John Joyce, a Republican from Pennsylvania, said his district is nearly 2,000 miles away from the border, but “illicit drugs continue to pour across the southern border and infiltrate into my district,” causing “addiction and death,” Joyce said.

Instead of passing Escobar’s bill, he suggested they return to committee and “work on a bipartisan basis to secure our border, to end the asylum loopholes, and to protect this great country,” Joyce said.

Border Patrol Agent Andy Adame waits for other agents to help process 78 border crossers found hiding under trees near Arivaca in 2007. Gary Gaynor, Tucson Citizen

In 2019, Escobar called for the creation of an ombudsman and border oversight panel, with one of various goals being to reduce migrant deaths. The bill passed the House. Sen. Tom Udall, a Democrat from New Mexico, introduced similar legislation, but it did not pass the Senate.

The exception to the rule was the Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains Act introduced by Cornyn in 2019, which became law after former President Trump signed it in December 2020. The law opened up grant funding to local governments and nongovernmental organizations to deal with migrant deaths and identify remains, although Cornyn ensured priority would not be given to the border area. The bill also funded more rescue beacons.

The law also requires CBP to file a detailed report with Congress and post it on the CBP website by the summer of 2021 about its efforts to count migrant deaths and mitigate those deaths, its collaboration with local governments and nonprofits, and the effectiveness of rescue beacons.

The bill passed the House on Dec. 16 after 10 minutes of debate in a nearly empty chamber. The speaker pro tempore, Rep. Henry Cuellar, a Democrat from Texas, called for a voice vote, but the few Congress members in the chamber didn’t respond. He had to ask them again, prompting a handful of “ayes.”

In other words, after 20 years and at least 3,900 deaths, the thrust of the first substantial action taken by Congress was to count how many migrants had died and to identify them.

Just one sentence

In his first days in office in late January, Biden pushed for broad immigration legislation to address a variety of issues.

When Democratic lawmakers introduced the 353-page bill in February, it contained just one sentence about migrant deaths, calling for more rescue beacons in the desert.

In a call with reporters days after the bill was introduced, several lawmakers responded to the Star’s question about how the bill would address migrant deaths but quickly veered off into other topics.

The bill addresses “certain concerns that our humanity compels us to address,” said Rep. Linda Sanchez, a Democrat from California who sponsored the bill in the House.

“Obviously, the deaths at the border, the rescue beacons are an important part of that,” Sanchez said. “But so is professional training for CBP and having medical training, having humanitarian standards for those that are detained, particularly for children and vulnerable populations.”

Sanchez said the “most exciting” part of the bill is that it addresses the root causes of migration, a thought echoed by Menendez, the New Jersey Democrat who sponsored the bill in the Senate.

“Yes, the beacon is only one example of modernizing and managing the border effectively with technology that enhances our ability not only to be humane but also to detect contraband and counter transnational criminal networks,” Menendez said.

The bill was introduced just as Border Patrol encounters with migrants started to accelerate dramatically. As those encounters reached historic highs, President Biden waved away concerns by telling a reporter at a March 25 press conference that the increase in migration “happens every single, solitary year” in the winter months.

“The reason they’re coming is that it’s the time they can travel with the least likelihood of dying on the way because of the heat in the desert,” Biden said.

Four months later, Biden’s words came back to haunt him politically, not because he had done nothing to address migrant deaths, but because border crossings continued to rise in the summer, which contradicted his claim that the rise in February and March was seasonal.

When Arizona Gov. Ducey deployed the National Guard to the border in late April, the Yuma County Sheriff’s Office issued a news release supporting Ducey’s decision and citing migrant deaths before any other concern related to the border.

When Department of Homeland Security officials announced a wide-ranging crackdown on smuggling organizations on April 27, they spent nine paragraphs talking about targeting the logistics of those organizations before ending with the line: “In Fiscal Year 2020, Border Patrol located 250 migrants who died during their journey.”

The exception to the legislative indifference to migrant deaths came in May when Escobar reintroduced her bill.

When Sen. Sinema came to Tucson on June 1 to promote her border bill, part of her pitch was the rising number of border encounters in Southern Arizona as the summer heat arrived.

As Sinema spoke to reporters at Casa Alitas, a shelter for asylum-seeking families in Tucson, about the importance of the bill she sponsored with Cornyn, she noted the “deadly” journey migrants make through Southern Arizona.

“The reality is that it’s getting more and more deadly every day as our temperatures are increasing,” the Arizona Democrat said. “And the routes, particularly in the Tucson Sector, as you all know, is very treacherous terrain and the number of search-and-rescue attempts are increasing every day.”

Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Sen. John Cornyn of Texas speak at Casa Alitas migrant shelter in Tucson in 2021. Rebecca Sasnett, Arizona Daily Star

The Star asked Sinema and Cornyn why they did not include any measures addressing migrant deaths in their bill. Both pointed to the rise in border crossings, rather than deaths in the desert, as the “immediate crisis” that needed attention.

Sinema said one goal of the bill was “jump-starting the conversation” to “target the immediate crisis that both of our states are suffering from.”

“This bill was meant to deal with the immediate crisis at hand, which has to do with asylum claims and our inability to process those claims in front of an immigration judge in a timely manner,” Cornyn said, noting the 1.3 million-case backlog in immigration courts.

“This was not meant to be a comprehensive immigration reform bill,” Cornyn said, adding, “this is no task for the short-winded.”

When Biden released his “Blueprint for a Fair, Orderly and Humane Immigration System” on July 27, the plan dealt with a wide array of issues. But not migrant deaths. Instead, Biden proposed more technology at the border and investment in ports of entry, along with measures to quickly remove migrants from the United States, discourage irregular migration, and target smugglers.

Migrant deaths appeared at the Nov. 3 hearing on the nomination of Tucson Police Department Chief Chris Magnus to head CBP.

Sen. Mike Crapo, a Republican from Idaho, noted the record-high number of encounters with migrants in fiscal 2021.

“Tragically, but not surprisingly, it also led to another record: the highest annual number of migrant deaths, 557 dead, trying to cross our borders,” Crapo said.

Meanwhile, back on the ground …

The lack of federal legislation related to migrant deaths has not gone unnoticed by aid volunteers in Southern Arizona, but it has not deterred them from continuing to try to reduce those deaths.

Watching politicians and lawmakers “really gets me down sometimes,” Dora Rodriguez said, as she drove back to Tucson after checking on a support center for migrants in Sasabe, Sonora, that she helped create this summer.

“But when I think I have a trip to Sasabe it pumps me up,” she said with a smile.

As she talked, she kept an eye out for signs of migrants in distress, pointing to black water bottles and discarded clothes in the dirt next to the highway, and to crosses marking where migrants died.

She said a “sea of volunteers” in Southern Arizona has helped pick up the slack by “doing the government’s job” when it comes to helping migrants in the desert.

She has firsthand knowledge of how deadly the border can be, and how necessary it is for someone to help migrants in distress. She crossed the border after fleeing El Salvador in the 1980s, but several of the people she was traveling with died during the crossing.

“For me, personally, this is a mission because I do this for my brothers that died the day that I was rescued,” Rodriguez said. “I think of that every day.”

Bill Busher, a volunteer with Humane Borders, carries a water barrel that will be left for migrants making their way through the open desert in Organ Pipe National Monument. Josh Galemore, Arizona Daily Star

Fourth of four stories

The deadliest season for migrants in Southern Arizona is over for this year.

It will start again in six months.

Officials and aid volunteers have taken numerous steps to reduce the number of migrants who die in Southern Arizona. But these deaths continue to mount, and broader, more proactive steps are needed.

Despite a broad consensus in favor of reducing those deaths and a wide array of well-intentioned efforts, rescues of migrants in distress are hampered by a lack of resources and leadership, poor record-keeping, difficulty in finding migrants in rough terrain in remote areas, and no clear rules for providing humanitarian aid, the Arizona Daily Star found after tracking migrant deaths and the responses to those deaths.

“We need to take death out of the equation,” said Dan Abbott, a volunteer with the group Humane Borders, as he refilled a water station at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument earlier this year.

The Star created the following series of recommendations for lawmakers and officials. They are based on clear patterns that emerge in data on migrant deaths, listening to lawmakers talk about those deaths, and speaking with migrants and people involved in responding to their distress.

1. Pass legislation specifically aimed at preventing the deaths.

Federal lawmakers and officials rarely address the large-scale deaths of migrants when it comes time to write legislation.

One step that likely would reduce migrant deaths would be federal legislation that shifts migration out of the desert and through ports of entry, such as a guest-worker program or visa reform. But that legislation may not be passed for many years, if ever.

Federal lawmakers are considering legislation to provide legal status to millions of migrants already living in the United States. Those bills do not directly address migrant deaths or migrants who have not entered the United States yet, but they do provide some form of legal status that could allow migrants already in the United States to visit family and friends in their home country and then reenter the United States through a legal port of entry, rather than risk their lives in the desert.

One such bill, the Farm Workforce Visa Modernization Act, would grant certified agricultural worker status to migrants who already work in the United States and allow them to legally cross the border. The bill passed the House in 2019 and was reintroduced this year.

Federal lawmakers should continue to try to pass legislation, as they have done since 2009, to direct Customs and Border Protection officials to study the relationship between border enforcement and migrant deaths.

Past legislative proposals included studying whether dangerous terrain contributes to migrant deaths, or even is an effective obstacle to illegal border crossings. That study could give lawmakers a better understanding of which types of legislation and resources are needed to reduce the number of deaths.

Lawmakers also should approve funds for hundreds, if not thousands, of rescue beacons along the border. Southern Arizona has about 34 rescue beacons in an area larger than several U.S. states combined.

The creation of an oversight panel made up of border residents and officials, as proposed by several lawmakers over the years, could shed more light on migrant deaths and foster a public conversation about how to reduce them. An ombudsman in the Border Patrol could create an official pathway for families to find lost loved ones and make complaints.

In the meantime, Congress should act with urgency to lessen the number of migrants who die in Southern Arizona, with the overall goal to bring those deaths to zero.

As the rising number of deaths shows, the officials who respond to migrants in distress need help. That help could come from the hundreds of volunteers in Southern Arizona who already have spent years trying to reduce migrant deaths.

As it stands, the rules for providing humanitarian aid are unclear and subject to change at the whim of officials at the Border Patrol or the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

Lawmakers abdicated their responsibility to establish rules for providing aid, leading to the current situation where it is legal to drive a hiker in distress to a hospital, but illegal to do the same for a migrant.

Congress could establish a framework for providing humanitarian aid appropriately and safely. The framework could establish protocols and training for volunteers, similar to the Sheriff’s Auxiliary in Pima County.

To fund those efforts, Congress could change the regulations on Operation Stonegarden, a federal program that funds overtime pay and equipment purchases by local law enforcement agencies that help with immigration enforcement, to allow some of those funds to be used for humanitarian efforts, in addition to law enforcement.

In July, Republican members of the House Appropriations Committee came up with a similar idea in a report on the Department of Homeland Security funding bill for 2022.

Among other measures, such as finishing the border wall, they unsuccessfully offered an amendment to “increase funds for Operation Stonegarden to help law enforcement agencies in border communities work with Customs and Border Patrol to rescue and apprehend migrants abandoned by the cartels,” wrote Reps. Kay Granger, a Republican from Texas, and Chuck Fleischman, a Republican from Tennessee.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency, which oversees Operation Stonegarden, already provided $2 million to Pima County to house and transport asylum-seeking families. County officials recently said those funds would be used to house asylum-seeking families at a local hotel if they were exposed to COVID-19.

Also this year, CBP awarded a contract worth up to $110 million to build a large tent-like facility in Tucson to house unaccompanied migrant children.

On a larger scale, CBP’s budget grew from $4 billion in 2003 to $15 billion this year. The Trump administration spent roughly $5 billion of Defense Department funds on 225 miles of border wall in Arizona in 2019 and 2020. The Obama administration spent more than $1 billion on a surveillance tower system in Southern Arizona that couldn’t detect illegal activity in the desert as it was designed to do and eventually was scrapped.

2. Build on data findings of the Star and other analysts by designating a team of University of Arizona researchers to analyze trends that could help focus rescue efforts in the deadliest areas.

The available data makes clear that migrants are dying in large numbers in Southern Arizona. But the scope of the disaster remains hidden, and far more data is needed to find solutions.

The Pima County Sheriff’s Department does not differentiate between rescues of migrants and rescues of hikers, stranded drivers and others. The Sheriff’s Department also does not retain 911 audio recordings for longer than six months, erasing a key public record of this humanitarian disaster.

The Border Patrol has made great strides in recent years when it comes to publishing data, but much more data is needed. The Star requested detailed data about migrant rescues, but Tucson Sector officials did not provide it.

CBP publishes monthly updates on the nationalities of migrants, whether they crossed as families, adults traveling alone, or children traveling alone, and the broad geographic area where they crossed the border.

CBP should do the same with rescues, migrant deaths, and the use of rescue beacons, some of which will be required next year by the Unidentified Remains and Missing Persons Act.

For more detailed information that would be vital to reducing migrant deaths, but which Border Patrol officials consider confidential, such as GPS locations of encounters with migrants, Congress could direct the Border Patrol to share that data with a team of researchers at the University of Arizona, some of whom have developed deep expertise by studying migrant deaths and migration in Southern Arizona for more than 15 years.

The UA researchers could agree to not release information in a manner that would compromise that confidentiality, just as officials and researchers collaborated to model the COVID-19 public health crisis.

The Department of Homeland Security designated the UA as a “center of excellence” a decade ago. UA researchers studied technology to detect deceptive answers from people at ports of entry; surveyed legal immigrants about their decision to migrate; modeled the effectiveness of Border Patrol checkpoints on highways, and other issues.

The UA researchers could combine data from the Border Patrol with data from county officials and humanitarian groups, such as the use of water stations on migrant trails. That data could be used to make public policy recommendations on how to save lives, such as real-time mapping of the most ideal water-drop sites or where to target search-and-rescue efforts.

Officials at the Pima County Sheriff’s Department could share GPS coordinates from 911 calls, which were included in the vast majority of calls reviewed by the Star. Border Patrol officials and sheriff’s departments could do the same with GPS coordinates from search-and-rescue efforts.

Incident reports from law enforcement agencies provide details on how officials responded to distress calls from migrants. Those reports could be sent to the UA team, where they could analyze trends in successful and unsuccessful responses.

The Border Patrol could share GPS coordinates from encounters with migrants in the Tucson Sector to show trends in migration, which would allow researchers to build models to predict where rescue efforts are most needed.

As the UA team refines its methods, similar collaborations could begin elsewhere along the border, such as the University of California-San Diego or the University of Texas-El Paso.

3. Designate an official to be in charge of rescue efforts.

Responding to migrants in distress in the wilderness of Southern Arizona is a difficult task, especially when distress calls come from 20 jurisdictions spread out over 27,500 square miles.

Local officials with sheriff’s departments and the Border Patrol have developed a system to respond to migrants in distress, but as the rising number of deaths shows, that system is inadequate.

Incident reports from local law enforcement show deputies and 911 dispatchers forced to waste precious time trying to figure out which agency should respond or deciding whether to respond to calls for help that were passed from a migrant’s family member to a humanitarian aid group and then to officials.

Perhaps the most striking inadequacy in the local response to migrant deaths is the lack of leadership and accountability. Border Patrol agents respond to hundreds of distress calls every year, but they are not formally responsible for rescuing migrants and those calls are not their top priority.

The framework established by Congress could put an official in charge of these efforts to bring together local and federal agencies, as well as humanitarian groups and county officials.

Each spring, that official could lead meetings to discuss what agencies and aid groups expect to happen that summer and how they intend to deal with it. They could come up with a plan for the summer and update it as more information becomes available about upcoming weather in Southern Arizona and changes in migration patterns.

Each summer, that official could coordinate rescue efforts, smooth out jurisdictional confusion, work with local humanitarian groups, and make sure families know what happened to their loved ones. At the end of each summer, that official could lead meetings to review rescue efforts and evaluate new measures put in place that summer.

For example, the Border Patrol is putting placards in the desert that migrants can use as reference points when they call for help, modeled after efforts by the Border Patrol in south Texas. The placards include a number and a three-letter code for each of the nine Border Patrol stations in the Tucson Sector.

At summer’s end, the official could gather data about how often migrants referenced those signs when they called 911, which signs were referenced more than others, and whether fewer migrants died in areas with more signs.

The official could share that data with the UA research team. If the data showed those signs were effective, the Border Patrol or aid groups could install more signs in specific areas of the desert over the winter months.

With the knowledge that the summer will bring deadly conditions every year for migrants, the official response to those conditions should evolve each year.

4. Expand cellphone coverage in the desert west of Tucson.

When migrants started dying in large numbers two decades ago, cellphones were far less common than they are today. Now, many migrants carry cellphones as they walk through the desert.

At the Border Patrol’s safety event in the summer, officials with the Border Patrol, Mexican Consulate, and Guatemalan Consulate urged migrants to call 911, but some migrants cross the border in areas without cell coverage or end up in mountainous areas where cell coverage is unreliable.

The remains of 84 migrants were found in areas without cell coverage since June 2020. Over the last two decades, the remains of more than 500 migrants were found in those areas, the Star’s data analysis shows.

The largest area without cell coverage is in and around the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge west of Ajo. More cell towers would help rescuers pinpoint locations of migrants in distress, as well as benefit rural communities. But few people live in that area, making it unlikely a cell company would invest in building cell towers. Instead, the federal government should pay for cell towers in those areas.

As the framework for humanitarian aid solidifies and the UA research team provides insight into search-and-rescue efforts, Congress could direct CBP officials to work with U.S. Fish and Wildlife officials, who run the Cabeza Prieta refuge, to expand cell coverage in that area.

The officials would determine the cost of building cell towers on or near the refuge, as well as figure out where cellphone towers could be built with the greatest impact on migrant safety and the smallest impact on the environment.

Officials also could expand the FirstNet system, a program of the U.S. Commerce Department to expand public-safety broadband networks for first responders. Federal officials awarded a multibillion-dollar, 25-year contract to AT&T in 2017. When the network is complete, it will cover 76% of the geographic area of the United States.

When needed, the agencies that use the system can request deployable assets to provide temporary coverage, “such as in remote and wilderness areas that will not have permanent coverage,” according to a 2020 report from the Government Accountability Office.

Without taking these steps, or finding better solutions, migrants will continue to die in a predictable and preventable crisis.

5. Congress should direct CBP to start processing more asylum seekers at ports of entry.

For the past decade, the Border Patrol has handled duties far removed from their core responsibilities of thwarting drug smuggling and illegal border crossings.

Today, agents are overseeing a facility near the Tucson International Airport where unaccompanied migrant children are held. Because asylum-seeking families often turn themselves over to agents in the desert, agents also have to spend an inordinate amount of time processing them.

Bagged bodies of migrants found in Southern Arizona are stored in a cooler at the Medical Examiner’s Office. Josh Galemore, Arizona Daily Star

The head of the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector, John Modlin, posted tweets in recent months calling attention to large groups of migrants, predominately children, who surrendered to agents on the Tohono O’odham Nation and near Sasabe. Agents must spend time transporting and processing those migrants, which takes away from their other duties.

At the same time, customs officers at ports of entry routinely turn away asylum seekers, despite ports of entry being a much safer and orderly place for asylum seekers to speak with officials.

The head of CBP’s Office of Field Operations in Arizona, Guadalupe Ramirez, told reporters in August that processing asylum seekers at ports of entry would disrupt trade and travel. In late September, a group of asylum seekers approached the port of entry in downtown Nogales to call for a return to asylum processing. Over the following few days, CBP officials placed large shipping containers in front of lanes at the port.

Rather than have asylum seekers risk their lives in the desert and force Border Patrol agents to spend time processing them, CBP officials should allow them to walk up to the port of entry in Nogales and make their asylum claims.

This could be done at the Morley Gate in downtown Nogales, a pedestrian-only port that closed during the pandemic. CBP officials could designate the Morley Gate for asylum seekers. As a site to quickly process asylum claims, officials could rent or buy one of the nearby stores.

Difficult Choices

Migrants who try to make it to Southern Arizona are faced with a variety of choices, none without risk.

They can wait for the Biden administration or Congress to change policies and allow them to ask for asylum. Families can travel to remote areas of the border and flag down Border Patrol agents and ask for asylum. They can give up on crossing the border and either stay in Nogales, Sonora, or return to their communities. They can try to cross the border undetected through the perilous desert and mountains.

If they wait for a change in policy, they risk extortion, violence and grinding desperation in towns on the Mexico side of the border. If they travel to remote areas and flag down agents, they may end up back in Nogales, Sonora, after officials return them under Title 42, the pandemic-related public health order.

If they give up on crossing, they may face relentless poverty or debts to smugglers they can’t pay off without making dollars in the United States. Worse still, they may face mortal danger if they return to their communities, such as the mafia that threatened migrant Joel Mondragon’s family, or a machete attack that left one woman with long, twisted scars along her left arm.

If they try to cross the border undetected, they put their lives on the line.

The choices migrants face in Mexico are mirrored on the U.S. side of the border by choices federal lawmakers, Border Patrol officials, and humanitarian aid volunteers face as they contend with the thousands of deaths and the extraordinary difficulty of rescuing migrants in the vast, harsh wilderness of Southern Arizona.

They can throw up their hands and say migrants broke the law when they crossed the border, and therefore their deaths are their own fault. They can embrace the moral obligation to make the best effort possible to reduce preventable deaths, regardless of citizenship.

While officials and lawmakers consider those choices, the death toll grows in Southern Arizona.

Those deaths, unfortunately, have become as predictable as the monsoon season, said Daniel Martinez, a sociology professor at the University of Arizona who has researched migrant deaths since the early 2000s.

“Next year, we’re probably also going to recover the remains of at least 150 to 200 people in our backyard,” Martinez said.

“This is not OK. This is not normal.”

Nearly 100 people walk along Sixth Avenue during a Dia de los Muertos procession to honor migrants who died in the desert crossing into the United States. Kelly Presnell, Arizona Daily Star